What’s new

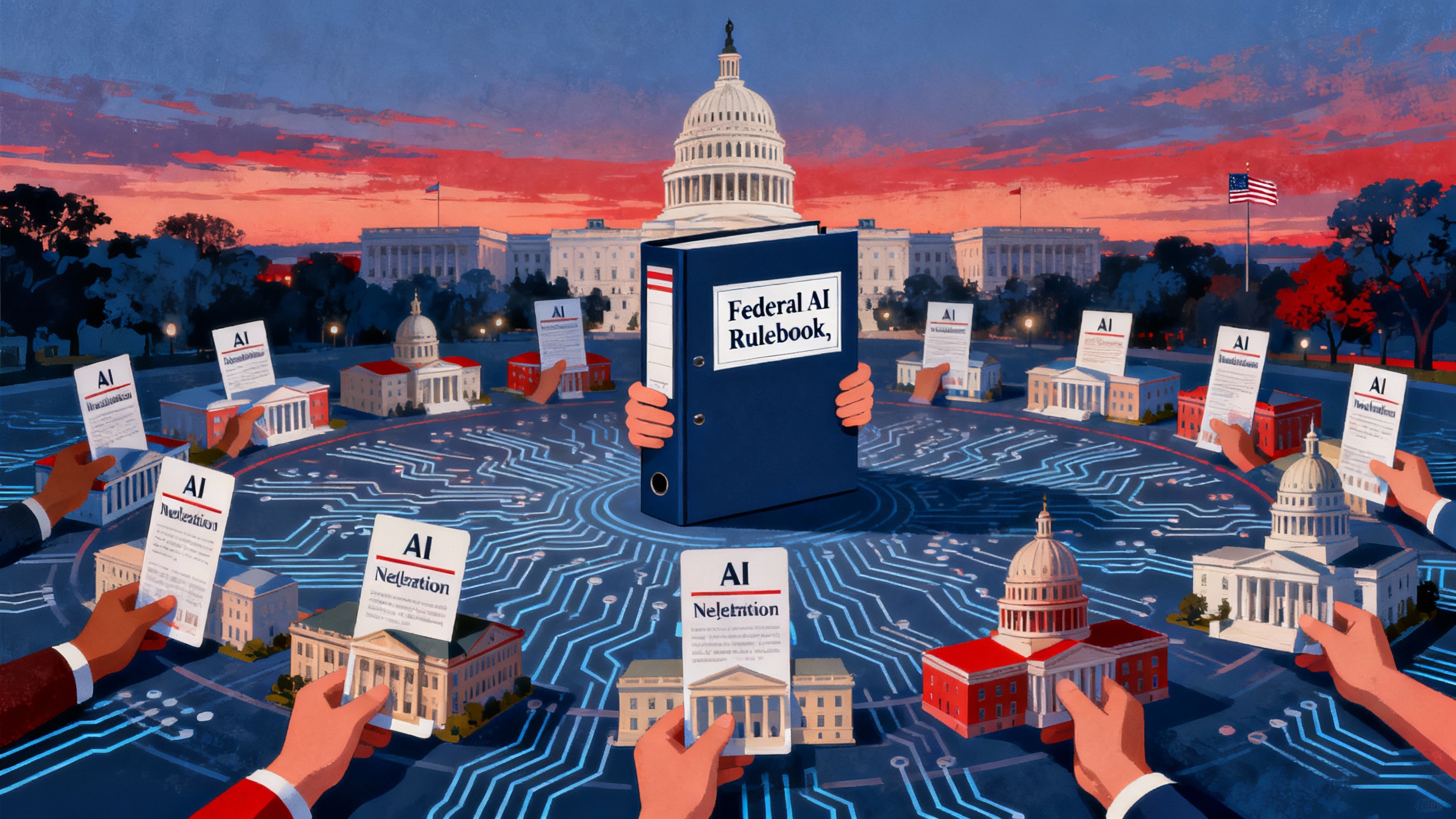

The White House has kicked off a push to create a single national AI “rulebook,” saying it will work with Congress on comprehensive legislation while moving immediately to challenge state-level AI laws it views as burdensome. An executive order signed on December 11, 2025, directs the Justice Department to form an AI Litigation Task Force, asks the Commerce Department to evaluate state AI statutes, and tells agencies to consider conditioning certain federal grants on states’ compliance with a future national framework. Reuters reports the administration will seek a “single national framework” for AI in the coming weeks and months. Reuters, Executive Order.

Why it matters

- For builders and buyers of AI, a patchwork of differing state requirements adds friction, cost, and legal risk. A single federal standard could simplify compliance—if it arrives through durable legislation and clear implementing rules. Reuters, U.S. Chamber.

- But executive action alone can’t instantly preempt states. Legal scholars expect court challenges, especially to funding conditions and dormant-commerce-clause claims. Any lasting “rulebook” will likely require Congress. Reuters, Washington Post Editorial.

The order at a glance

What the December 11 executive order does—and doesn’t

| What it does | What it doesn’t | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Creates an AI Litigation Task Force at DOJ to challenge certain state AI laws. | It does not by itself invalidate state laws; challenges will play out in court. | Lawsuits could narrow or block some state provisions, but outcomes are uncertain. Executive Order. |

| Directs Commerce to publish a 90‑day evaluation of state AI laws and identify “onerous” ones. | It does not set a federal compliance regime for companies. | A public inventory could shape Congress’s work on a national framework. Executive Order. |

| Tells agencies to consider grant conditions; BEAD broadband funds could be restricted for states with certain AI rules. | Does not guarantee courts will uphold funding conditions. | Conditioning funds is a powerful lever but faces legal risk. Reuters. |

| Asks FCC to explore a federal AI reporting/disclosure standard and the FTC to clarify when state mandates are preempted by federal deceptive‑practices law. | Does not immediately establish uniform reporting rules. | Could move disclosure obligations toward a single federal baseline. Executive Order. |

| Calls for a legislative proposal establishing a national AI framework with limited carve‑outs (e.g., child safety). | Does not replace Congress’s role in making national AI law. | Signals a pivot from litigation toward lawmaking for durable rules. Reuters. |

The patchwork the White House wants to replace

States moved first on AI rules, producing uneven obligations across sectors:

- California enacted the Transparency in Frontier Artificial Intelligence Act (SB‑53), requiring large “frontier” developers to publish safety frameworks, disclose risk assessments, and protect whistleblowers. California Governor’s Office, Latham & Watkins analysis.

- Colorado passed a broad AI Act in 2024 and later delayed and adjusted its effective date while debating key definitions. Colorado General Assembly, Greenberg Traurig.

- Utah narrowed its 2024 disclosure regime and added rules for mental‑health chatbots and deepfakes in 2025. Perkins Coie, Mondaq.

Industry groups argue these differences raise cost and chill adoption; civil‑liberties groups counter that state safeguards protect consumers where federal rules lag. U.S. Chamber, ACLU statement.

Inside the federal “rulebook” already taking shape for agencies

While Congress debates broader legislation, the federal government has been standardizing how agencies themselves use and buy AI:

- In April, OMB issued M‑25‑21 (governing agency AI use) and M‑25‑22 (AI procurement), updating Biden‑era guidance. M‑25‑21 keeps Chief AI Officers, sets governance boards, inventories use cases, and introduces a unified “high‑impact AI” category with stronger safeguards. M‑25‑22 tightens and standardizes AI acquisition. White House, Brookings, Defense Management Institute.

- Agencies are now publishing compliance plans and directives aligned to M‑25‑21/22 (e.g., EPA, Federal Reserve, GSA). EPA, Federal Reserve, GSA directive.

- NIST continues to provide technical underpinnings (e.g., an adversarial ML taxonomy) that agencies and vendors can map to procurement and risk programs. NIST.

Net effect: even before Congress acts, there is already a common federal playbook for how agencies should use and buy AI—one that contractors will increasingly be asked to meet.

Legal and political headwinds

- Dormant commerce clause: Past attempts to strike state tech laws on interstate‑commerce grounds have had mixed results. Expect years of litigation. Reuters.

- Funding levers: Tying broadband grants (BEAD) to state AI policies is a novel move that courts may scrutinize. Rural constituencies reliant on BEAD may also push back. Reuters.

- Politics: Some governors—including in GOP‑led states—have signaled resistance to wholesale preemption, favoring consumer‑protection tools they’ve already passed. Reuters, AP.

How the U.S. push compares to the EU’s AI Act

The EU already has a continent‑wide AI statute phasing in through 2026–2027, with earlier dates for prohibitions (February 2025) and general‑purpose AI obligations (August 2025). Whatever Congress drafts will inevitably be measured against the EU’s risk‑based approach, common definitions, governance bodies, and enforcement powers. European Commission, EU AI Office timeline, CSET.

What teams should do now

The bottom line

The White House is right that a unified approach would reduce friction and could accelerate safe adoption. But only Congress can deliver a durable single rulebook—and any federal standard will need to balance innovation with concrete protections for consumers and workers. Until then, expect continued state activity, court fights over preemption, and a steadily maturing federal playbook for how agencies use and buy AI.

Sources

- Reuters: White House will work with Congress on single framework for AI

- Executive Order: Ensuring a National Policy Framework for AI (Dec. 11, 2025)

- Reuters: Trump’s order targeting state AI laws faces political and legal hurdles

- AP News: Trump signs executive order to block state AI regulations

- U.S. Chamber: Applauds efforts to address patchwork state AI regulations

- ACLU: Statement on attack on state regulation of AI

- OMB policy updates: White House article on M‑25‑21 and M‑25‑22; Brookings analysis

- Agency compliance examples: EPA AI page, Federal Reserve compliance plan, GSA directive

- NIST: Adversarial ML taxonomy (2025)

- State actions: California SB‑53 (Governor’s Office; Latham & Watkins); Colorado (legislative update); Utah (Perkins Coie)

- EU comparator: EC AI Act overview; EU AI Office timeline